Experimenting With Rust and Java

Several years ago, I was introduced to the advantages of using Rust over other programming languages by a knowledgeable friend. While I had read about these benefits and heard other developers discussing them, I had not yet had the opportunity to personally experience or test Rust in a real-world scenario. As someone who prefers to work pragmatically on real-world problems driven by genuine needs, it wasn’t until I joined a large tech company with a highly concurrent, throughput-sensitive, and complex software system primarily implemented in Java that I was again met with the urge to explore Rust. However, given the existence of such a legacy system, a complete rewrite of the Java code into Rust is simply out of the picture. That’s why I decided to take a different approach and explore the possibility of integrating Rust piece by piece into our existing system.

This blog documents my first attempt at this problem.

Problem Statement

I wanted to begin with a problem that was given to me by the same wise friend who introduced me to Rust. Think of it as a LeetCode question, if you’d like, and maybe come up with your own solutions if you choose to follow along. Essentially, we want to calculate the value of π.

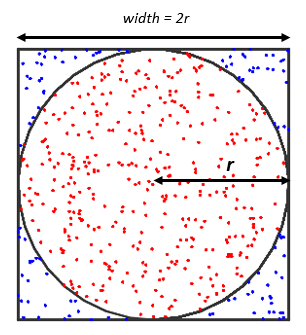

We decided to use a Monte Carlo simulation to estimate the value of π. In each iteration of the simulation, it generates a random point (x, y) within a square with a side length of 2, centered at the origin. Think of it as throwing darts. In the end, we want to see how many darts fell into a circle, and how many darts fell into the square.

After all iterations, the method calculates the estimated value of π using the formula: 4.0 * insideCircle / numIterations. This formula leverages the fact that the ratio of the area of the unit circle to the area of the enclosing square is π/4. By multiplying this ratio by 4, the method provides an estimate of π.

Now implmenting this in Java is straight foward.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public class PiCalculatorJava {

public static double calculatePi(int numIterations) {

int insideCircle = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < numIterations; i++) {

double x = Math.random() * 2 - 1;

double y = Math.random() * 2 - 1;

if (x * x + y * y <= 1) {

insideCircle++;

}

}

return 4.0 * insideCircle / numIterations;

}

}

Now, what if we wanted to implement this in Rust, and use it in Java? This mirrors the likley approach I’d be taking in my job if I were to start incorporating Rust in our codebase. So let’s see how that’s done.

Introducing Crate-JNI

Luckily for us, someone has already thought through this use case. A sample documentation can be found at crate-jni.

The way this works is by packaging the Rust code into a Java Native Interface Library, and then importing it in your Java applicaiton.

There are of course other ways to do this, notably using gRPC, RESTful APIs, etc. We’ll explore this at another time. For now, let’s stick with JNI, as this seems like the most intuitive way.

I created the following directory structure for this little experiment, following some conventions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

top_level_dir

- lib

- src

- rustSrc

- src

- lib.rs

- pi.rs

- Cargo.toml

I wanted to keep my java source code in the src directory. Afterall this is still a java project. rustSrc houses all my rust code. lib will house the exported JNI libraries that will be consumed by java.

According to the docs, we should start with our Java classes

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public class RunPi {

static {

System.loadLibrary("runpiwithrustandjava");

}

// Updated to include an int parameter

private native double calculatePi(int numIterations);

public static void main(String[] args) {

RunPi pi = new RunPi();

int iterations = 20; // Example number of iterations

System.out.println("Estimated value of PI with " + iterations + " iterations: " + pi.calculatePi(iterations));

}

}

Notice the difference between the native java implementation. Instead of actually implementing the method, we are essentially declaring the method signature, with the native keyword. This declares that the method calculatePi will be given by a native library.

When we consume the method, it’s as simple as using it like any java methods.

Naturally, we need to provide the actual implementation of the method in Rust. Here’s where the special handling comes in, as defined by the crate we are using. By the way, a Rust Crate is simply like a package, it is similar to a java jar, a npm module, or a python library.

According to the docs, we need to generate the type signatures for our method, by running javac -h . RunPi.java The result looks like this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

/* DO NOT EDIT THIS FILE - it is machine generated */

#include <jni.h>

/* Header for class RunPi */

#ifndef _Included_RunPi

#define _Included_RunPi

#ifdef __cplusplus

extern "C" {

#endif

/*

* Class: RunPi

* Method: calculatePi

* Signature: (I)D

*/

JNIEXPORT jdouble JNICALL Java_RunPi_calculatePi

(JNIEnv *, jobject, jint);

#ifdef __cplusplus

}

#endif

#endif

Using this we create our own Rust implementation. Navigate into RustSrc and create a new Cargo.

The docs don’t say but we should suffix our command with –lib. This is because we will be generating a library.

1

cargo new runpiwithrustandjava --lib

You should now see a lib.rs file and a Cargo.toml file.

Cargo.toml is a configuration file, similar to pom.xml for maven and build.gradle for Gradle in Java, or package.json for npm.

Here we add the dependencies we will be needing for our rust implementation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

[dependencies]

rand = "0.8.5"

jni = "0.21.1"

[lib]

crate_type = ["cdylib"]

The Rust Implementation

Inside your pi.rs implement the following.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

// This function calculates the value of Pi using a Monte Carlo method.

// It takes in the number of iterations as input and returns the calculated value of Pi.

// The function uses the JNI library to interface with Java.

use jni::JNIEnv; // Import the JNIEnv type from the jni crate

use jni::objects::{JClass}; // Import the JClass type from the jni crate

use jni::sys::{jdouble, jint}; // Import the jdouble and jint types from the jni crate

use rand::Rng; // Import the Rng trait from the rand crate

// This keeps Rust from "mangling" the name and making it unique for this crate

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "system" fn Java_RunPi_calculatePi(_env: JNIEnv, _class: JClass, num_iterations: jint) -> jdouble {

let mut inside_circle = 0; // Initialize a variable to keep track of points inside the circle

let num_iterations = num_iterations as i32; // Cast the num_iterations parameter to i32

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng(); // Initialize a random number generator

println!("Number of iterations: {}", num_iterations); // Print the number of iterations

for _ in 0..num_iterations {

let x: f64 = rng.gen_range(-1.0..=1.0); // Generate a random x coordinate

let y: f64 = rng.gen_range(-1.0..=1.0); // Generate a random y coordinate

if x.powi(2) + y.powi(2) <= 1.0 { // Check if the point is inside the unit circle

inside_circle += 1; // Increment the count of points inside the circle

}

}

println!("Number inside circle: {}", inside_circle); // Print the number of points inside the circle

4.0 * (inside_circle as f64) / (num_iterations as f64) // Calculate the value of Pi using the Monte Carlo method

}

Note we diverged from the doc and implemented our code in our own pi.rs file, instead of the lib.rs file. Either approach works when the libs we are defining are small and few, but when we want to define them on a large scale, it is better to define them in their own files and add them to the lib.rs file. We can do so by adding these to lib.rs.

1

2

mod pi;

pub use pi::Java_RunPi_calculatePi;

Now that we have our rust source code ready, we need to build our library, and release it to the wild. In the root of the cargo project (where the cargo.toml resides), run

1

cargo build --release

If all goes well, you should now see your dll under target/release/yourprojectname.dll. Copy over the dll into /lib.

Using it in Java

Finally, navigate back to the java source folder. We now need to compile our java code, and also providing where we should pick up our java libraries.

1

javac .\src\RunPi.java

You should now see our java class file in the src directory.

Next we provide the location of our own JNI lib when we run the java class. By deafult, Java looks for the java libraries in the system’s default library path. We are simply redirecting it to look at where we want.

1

java "-Djava.library.path=./lib" -cp src RunPi

You should see this output for 20 iterations

1

2

3

Number of iterations: 20

Number inside circle: 17

Estimated value of PI with 20 iterations: 3.4

Food for Thought

Now that we’ve successfully incorporated Rust into Java, congratulations are in order. But more importantly, we should ask ourselves, is this really better? Is Rust actually providing us with any sorts of benefit? To find out the answer to these questions. We should probably benchmark our native java implementation and our rust implementations.