Rethinking Technical Interviews: A Case for Practical Problem-Solving

When was the last time you wrote an algorithm from scratch?

Recently, a year and a half into my new software engineering job, I stumbled across the chance to utilize a binary search algorithm on a relatively simple problem. Initially, I could have implemented a straightforward $O(n^3)$ solution and moved on. Instead, I chose to refine the approach, spending considerable time optimizing it to $O(n^2 \log n)$. After an hour of code review, my colleague reviewed the code and found it overly complex. Given that the problem space n never exceeds 100, I ultimately reverted to the simpler $O(n^3)$ solution, thinking to myself, “Damn… Another opportunity to put all my LeetCoding skills to use gone…” Jokes aside, this experience led me to ponder the practical use of complex algorithms in everyday software engineering outside of academic exercises.

One of the most common questions I ask fellow software engineers is: “When was the last time you used a LeetCode-styled algorithm in your job?” Almost invariably, the answer is never. This isn’t to downplay the importance of algorithms—they are crucial for the high performance of many tools we rely on today. Yet, the reality is that we rarely expect, nor trust, nor enable junior engineers to implement such complex algorithms that could significantly impact system performance. Despite this, technical interviews remain heavily focused on such topics. Both interviewers and interviewees generally dislike these algorithm-oriented interviews; they often fail to accurately gauge a candidate’s potential as a software engineer.

Then why do we still do it? The prevailing justification for this focus is the supposed low cost of filtering candidates through standardized testing. Proponents argue that excelling in algorithm-oriented interviews correlates with high intellectual abilities and problem-solving skills. However, this is a flawed and unnecessary metric. Afterall, we aren’t interviewing hundres, or thousands of candidates. As a pre-screen measure? Sure. But as the final round of in-person technical interviews? Not a good idea. Many candidates simply memorize solutions to common LeetCode questions, undermining the fairness of this approach. Furthermore, the difficulty of questions can vary significantly, allowing some candidates to excel on easier problems while others falter on unfamiliar, harder ones. Even assuming that this method were unbiased, it still begs the question: What value does this filtering provide if the tested skills are seldom used on the job?

The Real Skills Needed

Software engineering is fundamentally about problem-solving: understanding an issue, breaking it down into manageable components, and systematically addressing each part. While LeetCode can test these skills to some extent, it primarily assesses candidates’ memorized knowledge rather than their ability to navigate new challenges. I argue that the latter is far more critical, especially when onboarding junior engineers.

What, then, would constitute a fair and effective system for hiring today’s top engineers? I propose an interview process that closely mimics real-world work environments and tasks. Rather than relying on abstract problems, we should leverage actual challenges the company faces. Previously, such a test was impractical without significant domain knowledge, which candidates couldn’t realistically acquire in a typical interview timeframe. However, with advancements in AI, candidates can now quickly gain a basic understanding of new domains. The ability to rapidly grasp and tackle new problems is a far better indicator of a candidate’s problem-solving prowess.

A Sample Interview Process

As an example, here’s a blueprint for one such interview process: Imagine you are interviewing a candidate for a web-based backend development role.

“Do you know anything about server-side rendering?”

“Yes!”

“Let’s try something else, what about HTTP3?”

“No, I don’t know much about it.”

“Great! I want you to build a SpringBoot application that utilizes HTTP3 protocol, you have 40 minutes. Explain your thoughts as you go along, you may use any tools you want.”

In this reimagined interview scenario, the focus shifts from theoretical expertise to practical problem-solving and adaptability. Consider a candidate faced with integrating HTTP3 into a SpringBoot application—a task they are unfamiliar with. This not only simulates an actual challenge they might encounter on the job but also levels the playing field for all candidates. After all, the goal is to gauge potential and adaptability, not merely pre-existing knowledge.

Now you can sit back, and observe how the candidate appraoches this problem.

What kind of questions do they ask? Are they simply copying and pasting this into chatGPT and have it formulate it? Are they digging deeper into any of the key areas, say into HTTP3 vs HTTP1.1/2? Are they quickly able to form a concrete understanding on these, and then apply them to solve the task at hand? What kind of clarification questions are they asking you, the interviewer? In the process of implementation, are they able to recall good design principles, and consciously consider algorithms, data structures and efficiencies? Are they able to communicate their thoughts clearly and concisely?

I argue that this is a much much better way. Other sectors have long recognized the value of this approach. In finance, candidates analyze real-world financial data to recommend strategies, providing insights into their analytical skills and business acumen. In consulting, the ability to solve actual business problems presented during interviews is paramount. These industries have proven that practical, scenario-based evaluations are superior in assessing a candidate’s potential and real-world effectiveness.

The Problem with Cheating

Now let’s come back to the problem of cheating. Addressing cheating, or the unfair advantage gained by preparation, is a perennial challenge in technical interviews. The traditional approach often leads to a high-stakes game where the incentive to memorize solutions is driven by the fear of losing out to others who might do the same. This environment fosters a scenario where candidates might go through countless standard LeetCode questions, learning the ‘correct’ answers by heart rather than truly engaging with the underlying concepts. Over time, this method tends to dilute the fairness of the process, as it relies heavily on a finite set of problems and solutions.

With the new approach, this is much harder. This new process significantly mitigates this issue by introducing domain-specific questions that are less likely to be known beforehand. This levels the playing field as it emphasizes how candidates adapt to and solve problems they haven’t seen before. Here, the focus shifts from what candidates already know to how quickly and effectively they can learn and apply new information. This approach not only tests their problem-solving skills but also their ability to innovate and think critically under pressure.

Furthermore, this method has the added benefit of detecting truly geinue domain expertise. If a candidate truly knows a lot about this idustry, you’ll figure that out by going through all the question you prepared, and hearing them confidently reply, “Yeah, I am familiar.” Well, you have yourself a junior hire with the domain knowledge of a senior. Feel free to hire them on the spot. Conversely, if a candidate attempts to gain an unfair advantage by pretending not to know about the problem, you’ll know by the way the formulate their questions.

Final thoughts

The development trajectory of generative AI illuminates a critical shift in our approach to machine intelligence. Initially, the focus was on creating highly specialized systems that excelled in narrow tasks by absorbing vast amounts of domain-specific data. This approach, much like candidates cramming for interviews, has its limitations. When faced with unfamiliar scenarios, both narrowly trained AIs and overly prepped candidates tend to falter, revealing the cracks in a foundation built on memorization rather than true understanding and adaptability.

In response, the AI field is evolving towards models like Retriever-Augmented Generation (RAG) and systems that use control codes or task-specific tokens. These tools enable AI to extend beyond its base capabilities and apply external tools and new information effectively. This shift underscores a significant insight: the value of an AI lies not just in what it knows, but in how swiftly and effectively it can adapt to new challenges and utilize new tools. Shouldn’t our approach to evaluating new talent mirror this philosophy?

Consider the limitations of a dedicated deep learning model that excels in recognizing cat pictures but fails to identify dogs. Similarly, a candidate who has mastered every system design and algorithmic challenge may struggle in real-world scenarios that demand flexibility and innovation. Why, then, do we persist with interview techniques that prioritize rote knowledge over the ability to engage with the unfamiliar and the unexpected?

Let’s redefine success in technical interviews not by how well candidates can recall solutions, but by how effectively they can navigate new problems with creativity and agility. After all, the real measure of a software engineer’s skill lies not in their ability to solve ‘Two Sum’ or ‘LRU Cache’ under controlled conditions, but in their capacity to contribute to a team and tackle genuine challenges they will face in the workplace.

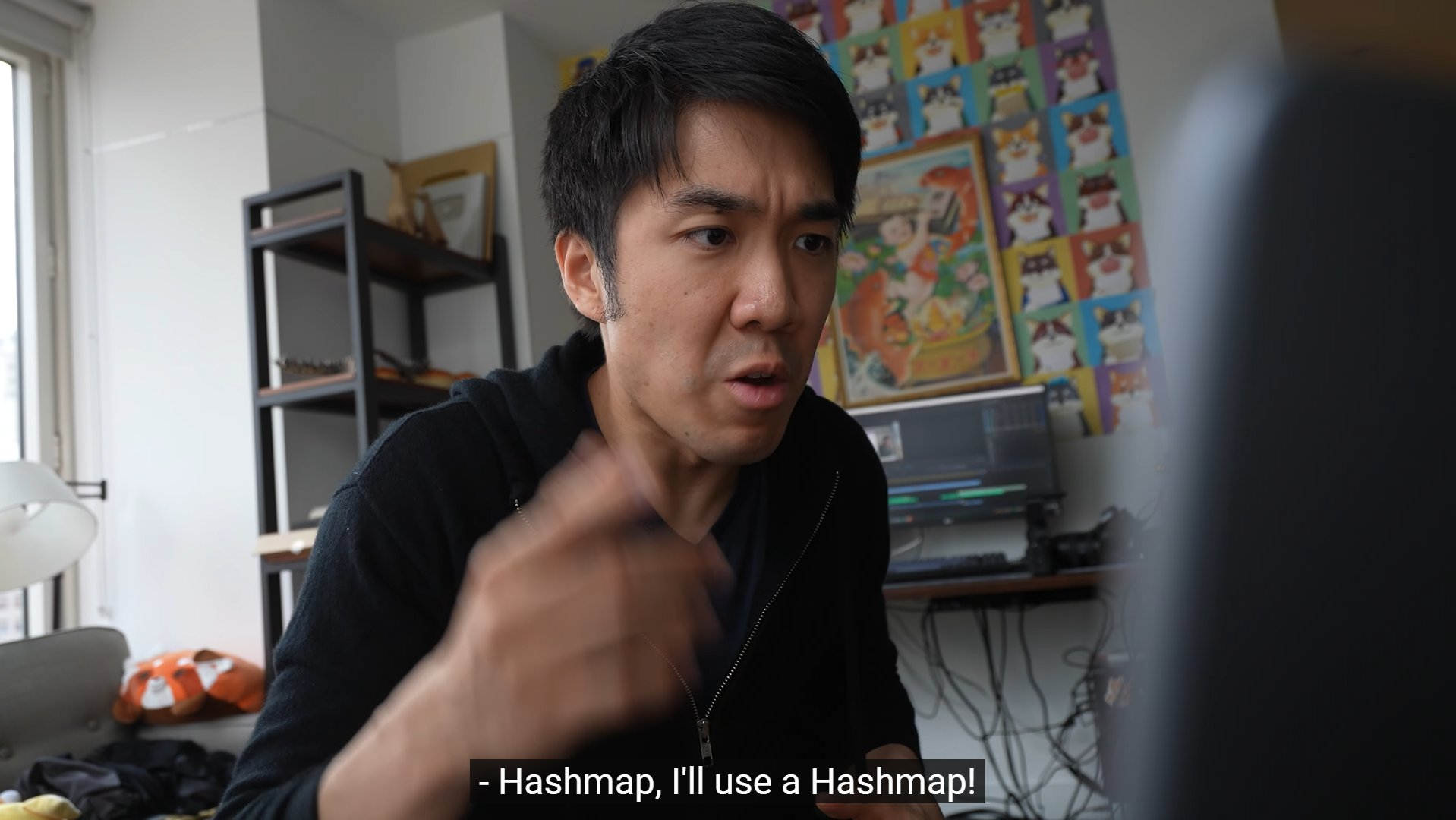

Perhaps, the next time we interview a candidate and ask them what are their thoughts on Object Oriented Programming, their response won’t be “HashMap”.

when my girlfriend asks me how i'm going to save our relationship pic.twitter.com/QcsDk91QXQ

— Siddhant Dubey (@sidcodes) July 23, 2022